Joost Termeer

Theme Park Europe

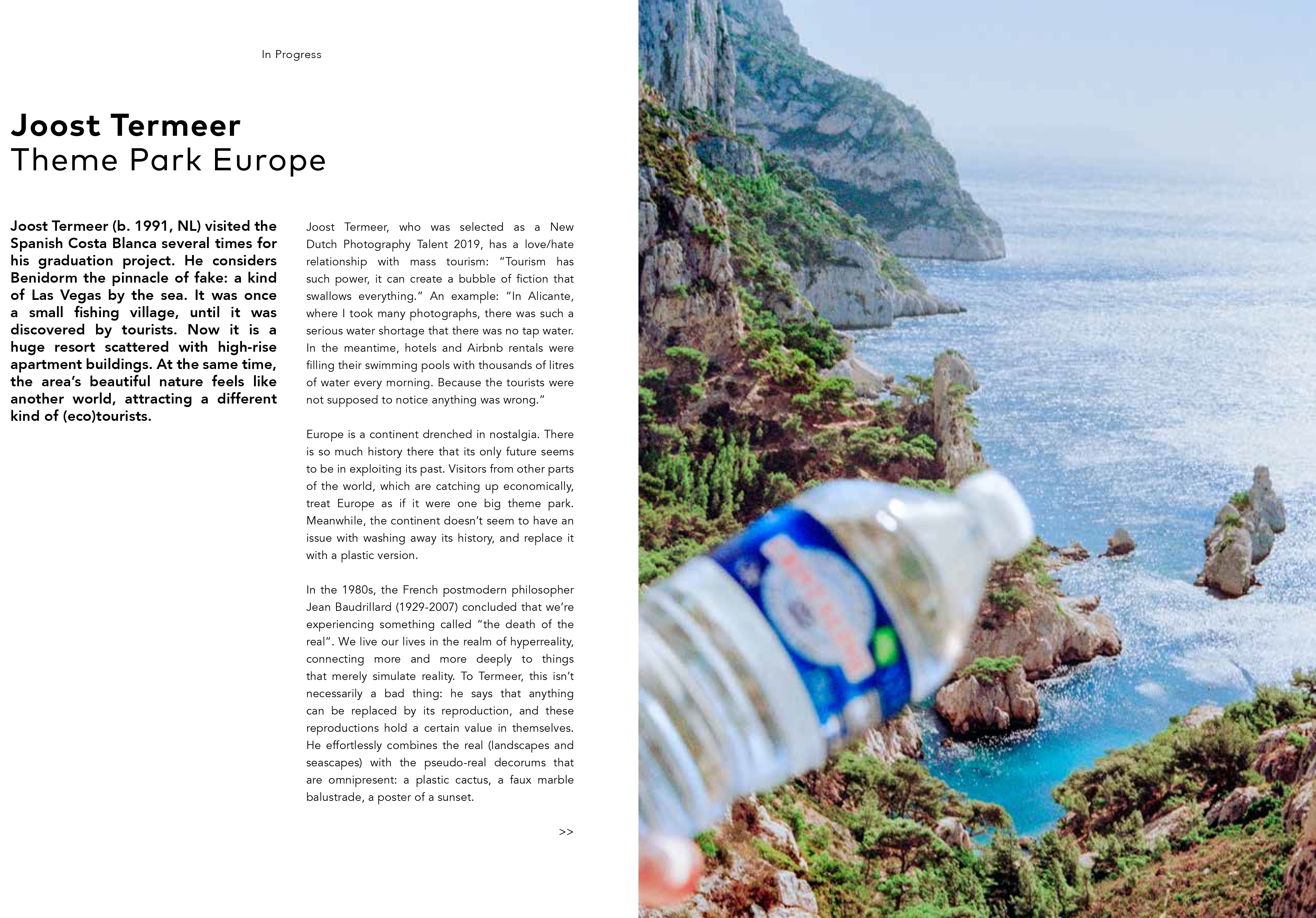

Joost Termeer (b. 1991, NL) visited the Spanish Costa Blanca several times for his graduation project. He considers Benidorm the pinnacle of fake: a kind of Las Vegas by the sea. It was once a small fishing village, until it was discovered by tourists. Now it is a huge resort scattered with high-rise apartment buildings. At the same time, the area’s beautiful nature feels like another world, attracting a different kind of (eco)tourists.

Joost Termeer, who was selected as a New Dutch Photography Talent 2019, has a love/hate relationship with mass tourism: “Tourism has such power, it can create a bubble of fiction that swallows everything.” An example: “In Alicante, where I took many photographs, there was such a serious water shortage that there was no tap water. In the meantime, hotels and Airbnb rentals were filling their swimming pools with thousands of litres of water every morning. Because the tourists were not supposed to notice anything was wrong.”

Europe is a continent drenched in nostalgia. There is so much history there that its only future seems to be in exploiting its past. Visitors from other parts of the world, which are catching up economically, treat Europe as if it were one big theme park. Meanwhile, the continent doesn’t seem to have an issue with washing away its history, and replace it with a plastic version.

In the 1980s, the French postmodern philosopher Jean Baudrillard (1929-2007) concluded that we’re experiencing something called “the death of the real”. We live our lives in the realm of hyperreality, connecting more and more deeply to things that merely simulate reality. To Termeer, this isn’t

necessarily a bad thing: he says that anything can be replaced by its reproduction, and these reproductions hold a certain value in themselves. He effortlessly combines the real (landscapes and seascapes) with the pseudo-real decorums that are omnipresent: a plastic cactus, a faux marble

balustrade, a poster of a sunset.

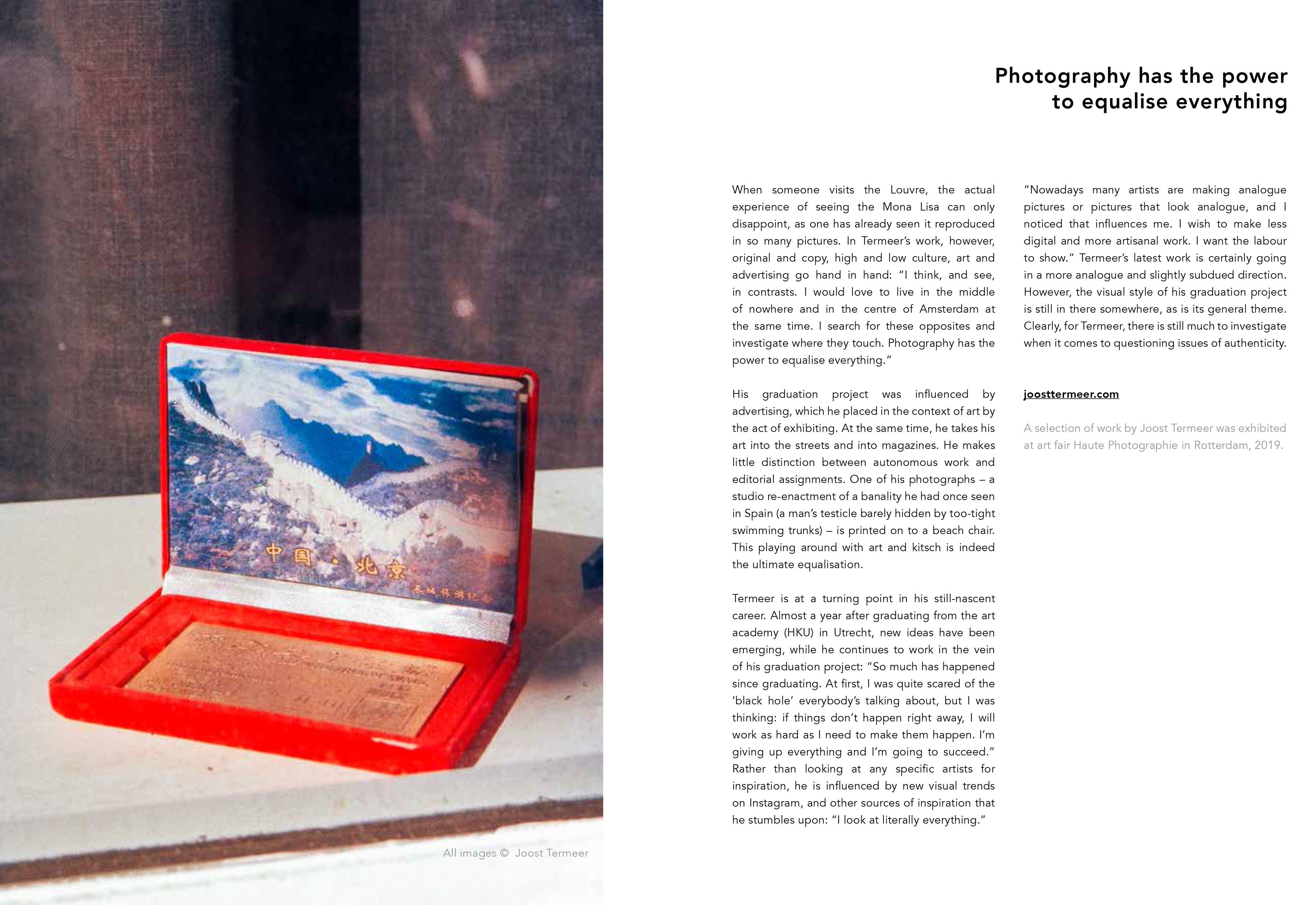

When someone visits the Louvre, the actual experience of seeing the Mona Lisa can only disappoint, as one has already seen it reproduced in so many pictures. In Termeer’s work, however, original and copy, high and low culture, art and advertising go hand in hand: “I think, and see, in contrasts. I would love to live in the middle of nowhere and in the centre of Amsterdam at the same time. I search for these opposites and investigate where they touch. Photography has the power to equalise everything.”

His graduation project was influenced by advertising, which he placed in the context of art by the act of exhibiting. At the same time, he takes his art into the streets and into magazines. He makes little distinction between autonomous work and editorial assignments. One of his photographs – a studio re-enactment of a banality he had once seen in Spain (a man’s testicle barely hidden by too-tight swimming trunks) – is printed on to a beach chair. This playing around with art and kitsch is indeed the ultimate equalisation.

Termeer is at a turning point in his still-nascent career. Almost a year after graduating from the art academy (HKU) in Utrecht, new ideas have been emerging, while he continues to work in the vein of his graduation project: “So much has happened since graduating. At first, I was quite scared of the ‘black hole’ everybody’s talking about, but I was thinking: if things don’t happen right away, I will work as hard as I need to make them happen. I’m giving up everything and I’m going to succeed.” Rather than looking at any specific artists for inspiration, he is influenced by new visual trends on Instagram, and other sources of inspiration that he stumbles upon: “I look at literally everything.”

“Nowadays many artists are making analogue pictures or pictures that look analogue, and I noticed that influences me. I wish to make less digital and more artisanal work. I want the labour to show.” Termeer’s latest work is certainly going in a more analogue and slightly subdued direction. However, the visual style of his graduation project is still in there somewhere, as is its general theme.

Clearly, for Termeer, there is still much to investigate when it comes to questioning issues of authenticity.